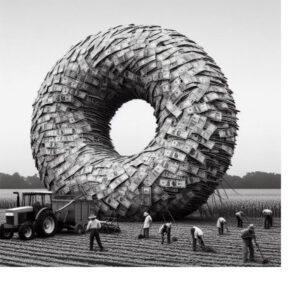

Single family offices should understand Lender Bagel structures and consider using them if they are not already. Knowledge of this structure has spread like wildfire since the landmark case, Lender Management LLC v. Comm’s. This article equips the reader with an understanding of the core principles of what Lender Bagel structures and how to investigate if it will help the family.

Single family offices should understand Lender Bagel structures and consider using them if they are not already. Knowledge of this structure has spread like wildfire since the landmark case, Lender Management LLC v. Comm’s. This article equips the reader with an understanding of the core principles of what Lender Bagel structures and how to investigate if it will help the family.

What Is It?

Lender Bagel structures (LBSs) are businesses owned by the family and in the trade or business of providing investment services to family investment vehicles. In short, it is a GP/Manager-like vehicle doing business only with the family.

The exclusive customer base and the active trade or business are the two things that distinguish an LBS from similar enterprises. If the enterprise does business with unrelated parties, it is not an LBS. A passive holder of investments, such as a family limited partnership, which does not provide services, is not an LBS. Finally, a single-family office is not an LBS even though it actively delivers services because the management of your own wealth is not a trade or business. (Higgins v. Commissioner)

When Should You Care?

When your single family office (i) delivers custom and competitive investment services that (ii) are quantitatively significant for tax deductions but (iii) are or will be denied utility because of the AMT calculationi, a properly structured LBS will harvest those denied deductions. While an LBS has practical benefits, most families will not take on the additional complexity and cost unless they harvest significant tax savings. Many families have the facts and circumstances required to support the deductions but lack the proper structuring to claim the deductions. Investigating an LBS will earn those families a benefit they already deserve.

What Is the Catch?

The tax savings are available when the LBS is a trade or business under IRC 162 and a profits interest compensates the LBS. Both items are tough nuts to crack.

Regarding the latter, the family does not own the LBS equally, which means some family members derive more economic benefit from successful investment management. If the family is uncomfortable with this arrangement, does not trust each other, or no one is actively engaged in investment management, then the LBS will not work.

Regarding the former, you need to demonstrate that the investment activities performed by these parties rise to the level of a trade or business. This questions “why” you undertake the activities and warrants more discussion.

Although businessmen and businesswomen conduct business to earn profits, the presence of profit is not quality evidence of business intent because not all businesses are profitable. Indeed, some hobbies are profitable but, nevertheless, are engaged in by the taxpayer for a reason other than to earn a profit. Historically, soliciting customers is the clearest evidence of business intent, which is the difficulty for LBSs.

Soliciting customers is not the only evidence of business intent nor a necessary consequence of a profit motive. A company conducts a trade or business even when not expanding its customer base. Moreover, for smaller organizations, such as single family offices, gathering customers is distracting. Doing so compromises the quality of their core offering and, therefore, they refrain from soliciting new customers. Additionally, there are regulatory issues to consider. Finally, building a customer base is a unique skill set. Businesses desiring constant growth will hire those professionals but a business that does not desire growth will not hire those professionals, which results in a static customer base.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, even in the caseii that found an active trade or business when the only customers were family, the court essentially took notice that the social relationship between much of the family is more like strangers than family. What, then, can be done for families that retain close familial relationships? What external and objective facts illustrate a trade or business other than the presence of seemingly or actually unrelated customers?

Unfortunately, there is no clear answer, yet. Some providers strongly recommend making the LBS a C Corp because they expect the IRS to treat every C Corp as an active trade or business. While C Corps are consistently treated as a trade or business, the reason for this is not derived from the form of taxation. In general, C Corps are deemed a trade or business because they are only used by larger operating trades or businesses not because they are taxed as C Corps. If the LBS falls short of 162 eligibility because it does not conduct a trade or business taxation as a C Corp should not change that conclusion.

What Should You Do?

A potential net financial benefit is a precondition for most families. Start with your CPA to learn what tax savings are possible if you correctly structure your investment affairs. Although an LBS delivers meaningful, practical benefits, it will absorb fees and time. Determine what investment costs the family incurs that are not deducted but will be deducted by the LBS.

If an LBS will produce a net financial benefit, map out the structure to build expectations of and comfort with the required cash flow. Then, identify and document the competitive skills, services, or offerings that justify treatment as a trade or business under IRC 162.

We encourage families to operate the LBS like you would a PE management company by establishing a business plan, a budget, and a company policy regarding the customer base that evidences the non-tax reasons for conducting business primarily (or exclusively) with blood relations. Wisdom suggests you develop the facts and circumstances evidencing the tax position before undertaking the activity.

If the structure produces a net benefit, the facts justify treatment as a trade or business, and circumstances allow the family to implement the LBS, hire an attorney to prepare and implement the necessary entities and documents. The final and ongoing step is the administration of the LBS, which is generally performed by key family members with the assistance of attorneys and reported by the family’s CPA.

i IRC 212 and other itemized deductions are suspended by the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act but will return 1/1/2026.

ii See Lender Management

ABOUT WEALTHGATE TRUST

Wealthgate Trust is a client-founded, Nevada-based, multi-family boutique trust company. Born from the founder’s own experiences searching for an ideal trustee solution for his family, Wealthgate Trust partners with ultra high net worth families and their advisory team to create, implement, and administer bespoke trust strategies.

Wealthgate Trust is licensed and regulated by the Nevada Financial Insurance Division (NFID), and audited separately by the NFID and two national CPA firms.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Aaron is Wealthgate Trust Company’s Chief Fiduciary Officer and Wealth Strategist, assisting families and their advisors in developing, implementing, and properly administering unique estate planning strategies. He is an attorney licensed to practice in California and Nevada, with over a decade of trust administration, trust planning, and tax planning experience. He can be reached directly at 702.781.8015 or by email, aaron@wealthgatetrust.com.

Reprinted with permission from Trusts & Estates Quarterly, Volume 23, Issue 2, Summer 2023.

“Paper tigers” are things that appear fierce but are harmless in practice. This terminology frequently appears in law. Statutes that prohibit an action but are backed by nominal penalties are paper tigers. Laws that are not enforced by judges are paper tigers. Some states write laws to favor trust makers but their judges often favor creditors, litigious beneficiaries, or the IRS. The trust advantages of these states are paper tigers.

Nevada is unique. Like a true tiger, which is as fearsome as it looks, Nevada’s trust laws are just as good in practice as they look on paper.

A perfect example of this is the Nevada Supreme Court’s decision In the Matter of The William J. Raggio Family Trust issued on April 9, 2020. In Raggio, after the trust maker’s death, the trustee could distribute to the surviving spouse as much as the trustee deemed “necessary for [her] proper support, care, and maintenance…” The remainder beneficiaries of the trust, the trust maker’s two daughters, desired to preserve as much for their future benefit as possible by limiting current distributions to the surviving spouse. Because the trust document did not explicitly support their argument the daughters used another source to support their fight.

The daughters relied on the Restatement (Third) of Trusts, which is a powerful legal treatise written by legal scholars, professors, and judges. It is not specific to any state and is frequently used by judges across the country to resolve disputes. It is the Ivory Tower of legal rules and expresses, in comment (e) of §50 that the surviving spouse’s other resources limit what she receives from the trust. In essence, she must utilize her outside resources before receiving a distribution from the trust.

If you are going to purposely select a state for a legal competitive advantage, such as flexibility, security, or taxation, it is imperative that the advantage is actually available.

In the other corner, the surviving spouse countered with a rather simple argument: Nevada law specifically prohibits what the daughters’ want. Nevada Revised Statutes 163.4175 provides:

Except as otherwise provided in the trust instrument, the trustee is not required to consider a beneficiary’s assets or resources in determining whether to make a distribution of trust assets.

In short, the surviving spouse may receive distributions from the trust her husband left her without first exhausting her separate assets.

In this battle between the Ivory Tower and Nevada law, the Nevada Supreme Court ruled definitively in favor of the latter. Indeed, its opinion takes note that the Nevada legislature specifically considered and rejected the Restatement (Third) of Trusts’ position. This decision illustrates that Nevada’s favorable trust laws are not paper tigers.

This same sentiment appeared a few years earlier in another hotly contested, public case. In Klabacka v. Nelson (2017), a creditor attacked the assets of a debtor’s Nevada Asset Protection Trust (“NAPT”). Forty-eight of the fifty states would require the NAPT to pay this type of debt and the creditor argued that the court should follow the principles of the rest of the country. The court disagreed and said this about Nevada:

Despite the public policy rationale used in other jurisdictions, Nevada statutes explicitly protect [NAPTs] from the personal obligations of beneficiaries. … The legislative history of [NAPTs] in Nevada supports this conclusion. It appears that the legislature enacted the statutory framework allowing [NAPTs] to make Nevada an attractive place for wealthy individuals to invest their assets … the Legislature contemplated a framework that protected trust assets from unknown, future creditors…

This case proves that Nevada’s highest court knows Nevada’s laws are drafted to provide trust makers with unique advantages and that the court is going to enforce those laws.

In contrast, the infamous Alaska decision in Toni 1 Trust v. Wacker (2018) illustrates a classic paper tiger. Alaska, which markets itself as a superior trust jurisdiction, enacted a law intended to control attacks by creditors from other states. This law is similar to those found in many international trust jurisdictions and provides that disputes regarding an Alaska trust must be litigated in Alaska. In essence, the Alaska legislature instructed its courts to exercise their own discretion and not rely upon judgments from other states. When the creditor obtained an order from a Montana judge requiring that the trustee turn over the trust assets to the creditor, the trust maker asked the Alaska court to require that the matter be litigated in Alaska. Even after acknowledging that this request is precisely what the law was designed to do, the Alaska Supreme Court decided against him, allowing the trust assets to be taken.

Knowing that a court can set aside the law, as this case illustrates, there is no sentiment more valuable to the trust maker than believing that what (s)he wanted done will be done. If you are going to purposely select a state for a legal competitive advantage, such as flexibility, security, or taxation, it is imperative that the advantage is actually available. You put your trust in Nevada because you can rely upon Nevada to follow the law.

You put your trust in Nevada because you can rely upon Nevada to follow the law.

Nevada offers a host of competitive advantages. Famously, Nevada offers tax relief and asset protection. In addition, some families desire to foster principles of self-reliance in their heirs by withholding confidential information regarding the inheritance until the time is right, which Nevada allows. Another common concern is that the costs of administration and litigation will consume the trust assets. Nevada law provides streamlined alternatives to cut down on unnecessary costs and litigation, such as nonjudicial avenues to resolve disputes and solve an unforeseen crisis. These benefits are only as good as the court who enforces them and, as we have seen, Nevada judges enforce Nevada law.

Furthermore, Nevada laws are often enhanced because it seeks to be the best jurisdiction for wealthy trust makers. These laws, while enacted by the legislature, are authored by nationally recognized trust and tax planning attorneys who know best what benefits the wealthy trust maker seeks and needs.

Considering that it usually takes decades for a new law to be challenged in court, that progressive trust laws are relatively young in the United States, and that Nevada will continue to enhance its laws, these Nevada Supreme Court decisions carry significant value. They testify to the direction a court will lean regarding future challenges, even as it relates to future laws, giving trust makers a peace that is not offered by the other states who have negative cases or no supporting cases.

When it comes to trust planning, implementation and enforcement of a trust maker’s wishes, Nevada courts have made it clear that in Nevada, you will find no paper tigers.

Wealthgate Trust is a client-founded, Nevada-based, multi-family boutique trust company. Born from the founder’s own experiences searching for an ideal trustee solution for his family, Wealthgate Trust partners with ultra high net worth families and their advisory team to create, implement, and administer bespoke trust strategies.

Wealthgate Trust is licensed and regulated by the Nevada Financial Insurance Division (NFID), and audited separately by the NFID and two national CPA firms.

Aaron is a Wealth Strategist assisting Wealthgate Trust families and their advisors in developing and implementing bespoke estate planning strategies. He’s an attorney licensed to practice in California and Nevada, with over a decade of trust and tax planning experience, and presents on a variety of topics including wealth preservation and private trust companies.

Aaron previously served as the primary tax planning counsel for Lobb & Plewe LLP. He has represented several major trust companies and sits on the board of the Coalition for American Retirement. Aaron earned his JD from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Wherever you find significant wealth you find significant taxes. At death you find a wealth-destroying tax: the Estate Tax. Presently, when the tax applies, it exacts 40% of your net worth, payable within 9 months of your passing. Current legislative proposals aim to apply the tax to more of your wealth and increase the tax rate to as high as 65%. You cannot take your wealth with you when you die and the government won’t let you leave it behind either.

The nature of the Estate Tax is quite different from other taxes, such as the Income Tax. The Estate Tax is imposed because of something that happened to you, something you avoided at all costs – dying. On the other hand, the Income Tax is imposed, in almost all cases, because of something you did – generate income.

Income Tax comes because you accrue a new benefit and it can be paid from the benefit received, preserving the original value. Tax on rental income is paid from the rent receipts. Gains from the sale of appreciated stock is paid from the appreciation. Estate Tax, however, carves out a portion of all the property, both the original value and the appreciation. It strikes with unbiased precision and the expensive bill must be paid quickly. As a result, in order to generate sufficient liquidity to pay the tax, businesses, investments, and real estate are often sold by your heirs at fire-sale values.

The title to a recently proposed Estate Tax reform bill, “For The 99.5% Act,” describes precisely who Congress targets with the Estate Tax: the ultra-high net worth individual. The Estate Tax is lethal to this individual and it cannot be ignored. You must acknowledge it, understand it, and address it. Fortunately, your options are quite simple. The Estate Tax is imposed on the transfer of property owned at death. Therefore, you address it in one, or both, of two methods: (i) limit what you own at death or (/i) carefully select who you give it to.

Although the Estate Tax is imposed on all of your assets, it allows you to deduct the amounts you give to charity and the amounts you give your spouse. Transfers to charities are never taxed. If you transfer all of your wealth to charity you pay zero tax. Transfers to a spouse are not taxed at your death but, instead, at the death of your spouse. In essence, gifts to a spouse delay the tax, they do not reduce it.

Consequently, most planning reduces Estate Tax by limiting what you own at death. The simplest form of this planning is spending. For the ultra-high net worth, the true targets of the Estate Tax, their wealth is too great to spend away. Alternatives are necessary.

The oldest, easiest, and most obvious alternative to reduce your Estate Tax was gifting assets during life. It was so obvious and easy that Congress quickly reacted by imposing the Gift Tax in 1924 and overhauling it in 1932. Because it imposes a tax on the transfer of property during life, planning options had to evolve.

One common evolution is to take advantage of the difference between the legal value of something and the value your heirs receive. When the legal value is lower than what the heirs receive (the difference is referred to herein as the “Delta”), you can transfer the Delta without incurring Estate or Gift Tax.

Sometimes this happens by taking advantage of time. You transfer assets early-on at present value and incur the tax at that time. The appreciation in the assets that occurs between the transfer and when the heirs inherit – the Delta – is free of Estate and Gift Tax.

Another method uses the time-value of money to lower the value of the assets transferred. When you transfer assets to a trust that provides your heirs with inheritance at the end of a term of years, the value of that gift is less because the heirs must wait for the inheritance. The Delta is the difference between the present-value of the future gift and the value of the gifted assets today. This Delta transfers Estate and Gift Tax free.

A different evolution uses legal realities to reduce the value of an asset at the time of transfer. For example, the owner of all of a $30M commercial building has all the rights to the building. But the owner of 50% of the same building must share those rights with the other owner(s). Because the rights are shared, you must involve others in deciding to lease the building, make improvements, or sell, to name a few. Because others share these rights, it is more difficult to sell the 50% interest and because the interest is more difficult to sell, it warrants a lower price or value. You transfer 50% of the real estate to a trust for your children for a value much lower than $15M (50% of $30M) and that difference is the Delta, which transfers free of Estate and Gift Tax.

Another strategy uses specially designed trusts to limit the assets you own for Estate Tax purposes but still treat you as the owner for Income Tax purposes. Initially, this seems unattractive but it is one of the most effective wealth-transfer strategies. Because you are personally responsible for the Income Tax, you can pay the tax from your personal assets, further reducing what you own that is subject to Estate Tax, meanwhile the trust’s assets, which you do not own when the Estate Tax is calculated, will grow Income Tax free.

Nearly all planning utilizes several of these tactics but, unfortunately, many of them are under attack in the For The 99.5% Act and could be eliminated. Some will be “grandfathered in” should you implement the strategy before enactment. While last year saw an enormous amount of planning because of one expected change to Estate Tax, this year should see ten to a hundred-fold as much planning because multiple changes are now proposed. It is a grievous error to delay planning.

These are strategies the ultra-high net worth individual will implement whether or not the For The 99.5% Act passes, therefore the question isn’t “Should I act?” but “When?” The time is now.

Wealthgate Trust is a client-founded, Nevada-based, multi-family boutique trust company. Born from the founder’s own experiences searching for an ideal trustee solution for his family, Wealthgate Trust partners with ultra high net worth families and their advisory team to create, implement, and administer bespoke trust strategies.

Wealthgate Trust is licensed and regulated by the Nevada Financial Insurance Division (NFID), and audited separately by the NFID and two national CPA firms.

Aaron is a Wealth Strategist assisting Wealthgate Trust families and their advisors in developing and implementing bespoke estate planning strategies. He’s an attorney licensed to practice in California and Nevada, with over a decade of trust and tax planning experience, and presents on a variety of topics including wealth preservation and private trust companies.

Aaron previously served as the primary tax planning counsel for Lobb & Plewe LLP. He has represented several major trust companies and sits on the board of the Coalition for American Retirement. Aaron earned his JD from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Wealthy families learn from difficult and costly experience the unintentional and adverse consequences of using family members as trustees. Famous family disputes make news and it is easy to be hoodwinked by notoriety into thinking, “This doesn’t happen to people like me.” The reality is the same issues, emotions, and stresses play out in every family; the only thing that differs is “how” it plays out.

In July of 2014, Pat Bowlen, NFL Hall of Famer, stepped down as owner of the Denver Broncos for health reasons. His trust’s Board of Trustees, which included his estate planning attorney and two Bronco executives, were required to select one of his seven children to act as controlling owner of the Broncos. No controlling owner was appointed and, unsurprisingly, disputes over who should control followed, which escalated into a dispute over Pat’s competency to create the trust.

You can view the matter as a dispute over Bowlen’s capacity, nothing more. Or as a manufactured claim by a disappointed child. You can blame Pat for failing to personally select a child before stepping down. Or you can blame the Board of Trustees for not choosing someone sooner. All of these natural reactions, regardless of whether they are right or wrong, miss the true source of conflict, namely, involving family in the management of a large estate.

This source of conflict extends to the entire family, not just the immediate members, and includes management of any source of wealth whether it’s controlled by a trustee or not. In Pat’s case, his trust is managed by a Board of Trustees, none of which are relatives but at least two of which are very close to the family and heavily invested in the primary source of wealth, the Denver Broncos. Furthermore, the trustees’ duty is to select one child to govern that dynasty for all the other siblings, a task which inevitably creates competition, jealousy, and resentment. Often, family members are selected to govern because they are emotionally connected to the beneficiaries and the estate. Unfortunately, the unintended consequence of this is that all decisions, including those based on economic, personal and legal positions, are dictated by emotion.

Sometimes, multiple family members are asked to serve jointly to assuage bias, even-out personality differences, or provide checks and balances on decisions. Unfortunately, forcing individuals to work together when they have diametrically opposing views usually results in that division widening, not closing. The trust and beneficiaries suffer.

For example, Alex and Faye Spanos, owners of the San Diego (now Los Angeles) Chargers both passed away in 2018. Following their deaths, 36% of the team was owned by their trust, held for the benefit of their four children with two of the children, Dea and Dean, serving as co-trustees of the trust. Dea’s and Dean’s opposing views regarding the Chargers came to a head in April of 2021 when Dea sued her brother and other siblings to force a sale for alleged economic reasons. She cited debt in excess of $350,000,000 with projections for large annual shortfalls. Dean and his siblings responded to the suit with a statement expressing that they understand the Chargers are a key family legacy and Dea is motivated by misguided personal agendas.

This example illustrates what happens when you place emotionally invested persons in charge of emotionally charged issues. The point isn’t that Dean should not care about the emotion or that Dea should not care about the economics. Their caring is natural, unavoidable, and should not be ignored, but also shouldn’t be utilized. The use led to more division, which led to a likely expensive and even more polarizing lawsuit. A wiser course for the wealth creator is to place an independent party in charge of the desired family objectives. Then an unbiased party can make unemotional, prudent economic decisions. Otherwise, you have emotions dictating actions, which leads to poor results.

In our experience, a death in the family drastically alters family dynamics and it is impossible to predict how family will react. Events, such as reaching a certain age, large distributions, and deaths in the family, often spurn family members into acting on grudges. Liesel Pritzker sued her father, the trustee of several family trusts (including her own) for $6,000,000,000 She alleged he misappropriated trust funds, arguing, in part, that he was motivated to do so by an eight-year-old family dispute that spurned her parents’ divorce.

Every wealth creator wants the estate plan honored and wants to limit adversity. Unfortunately, no matter how much you plan, you cannot perfectly predict every scenario. A hostile beneficiary will always find something to argue about. If you can keep family out of the governing roles, you can at least eliminate family baggage and reduce damage to relationships.

Choosing family because they are low-cost invokes the old adage that, “You get what you pay for.” An often-overlooked consequence of free labor is that it generates resentment and hostility, especially when the quality or skill of that labor is questioned. Disappointed beneficiaries expect perfect performance regardless of the fee charged or the skill of the fiduciary. The law provides a myriad of claims to raise, including but not limited to, breach of fiduciary duty, duty of loyalty, self-dealing, and failure to behave as a prudent investor. Failure to use a professional often generates disputes, which risks squandering the estate on legal fees, as each of the aforementioned examples illustrate.

Finally, consider the personal liability to which family-member-trustees are subject. Unfortunately, prolonged familial interaction accustoms members to providing a cost-efficient standard of care and communication. Additionally, extensive, intricate knowledge regarding the beneficiaries imbues the trustee with greater ability and, therefore, greater liability. It is quite common for well-meaning family trustees to fall short on technicalities, subjecting them to significant personal liability. For example, little nuances, like failing to include your address on a notice or failing to include a summary of an accounting with the accounting, can cause significant consequences. Historically, family members with foresight resign once they realize the terrible situation created by using family as a trustee. A member of Walt Disney’s family resigned once she learned what decisions the role required. Others did not and several years later a $200,000,000 suit arose.

For the most part, trusts are designed by family to benefit many generations of family, which is a wonderful desire and one worth honoring. However, using family to administer the trust agreement often causes much more harm than good. Rather than family, a reliable, disinterested, and professional corporate trustee should manage the trust estate. Boutique, corporate trust companies provide a tailored solution for families with legacy and complex issues that require high-touch connections, reporting, and responses. Wealthgate Trust Company, the institution behind this article provides services to a limited group of ultra-high net worth families, which allows it to maintain a high level of individualized service, take on unique asset classes or concentrations, and mitigate the risks associated therewith. Using them mitigates the family conflicts and adverse consequences that victimized the Prizkers, Disneys, Bowlens, and Spanos.

Wealthgate Trust is a client-founded, Nevada-based, multi-family boutique trust company. Born from the founder’s own experiences searching for an ideal trustee solution for his family, Wealthgate Trust partners with ultra high net worth families and their advisory team to create, implement, and administer bespoke trust strategies.

Wealthgate Trust is licensed and regulated by the Nevada Financial Insurance Division (NFID), and audited separately by the NFID and two national CPA firms.

Aaron is a Wealth Strategist assisting Wealthgate Trust families and their advisors in developing and implementing bespoke estate planning strategies. He’s an attorney licensed to practice in California and Nevada, with over a decade of trust and tax planning experience, and presents on a variety of topics including wealth preservation and private trust companies.

Aaron previously served as the primary tax planning counsel for Lobb & Plewe LLP. He has represented several major trust companies and sits on the board of the Coalition for American Retirement. Aaron earned his JD from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

Deciding between using a private trust company (PTC) or a corporate trustee is like pairing a wine to the main course. Many objective factors inform the decision but it is always determined by the diner’s personal taste. Similarly, certain legalities and realities direct the structure and management of private and corporate trust companies but choosing between them will be based on preference.

Corporate trustees are for-profit organizations providing fiduciary services to third-parties. A corporate structure provides families with independence and professionalism through an enduring business entity. Furthermore, corporate trustees are highly regulated by both State and Federal agencies to assure that the company performs properly and safely secures assets. Using an independent body to make important trust decisions, such as if, when, and in what amount to distribute to beneficiaries, ensures that the decision is made fairly, without bias or neglect. They are generally staffed by experienced attorneys, CPAs, and professional investment managers. For these reasons, and others, many families select a corporate trustee to protect their family, their wealth, and their legacy.

Unfortunately, some corporate trustees are sluggish, impersonal, inflexible and unnecessarily risk-adverse. These traits appear more often, and more severe, in larger organizations, thus ultra-high net worth families look for nimble, cooperative, yet safe alternatives. The two most common substitutes are boutique, corporate trust companies and PTCs.

A PTC is an organization permitted by a select few States to provide trustee services to a single family of related trust entities. Most of the time it is an LLC and operates at-cost instead of for-profit. It is organized and implemented to service the family’s trustee needs and, in general, is staffed by members of the family. The organization is regulated by the State but subject to less scrutiny and, therefore, less safety-measures. Also, PTCs are subject to certain Federal regulation and IRS guidelines, the violation of which incurs the wrath of fines and penalties and can jeopardize your entire estate plan.

Many trusts provide tax and asset protection advantages that are obtained only if the trust is administered properly. The IRS provides guidelines for proper administration, which require unrelated and disinterested third parties to hold relevant powers, possess private information, and be paid reasonable rates for these services. In short, the IRS requires the PTC to bear similar formalities as a corporate trustee or you will lose the benefits of your estate plan.

Additionally, if the PTC performs securities-related investment management it must be registered with the SEC. Registration with the SEC is expensive and onerous, which prompts many to seek an exemption from registration. Unfortunately, to comply for the SEC family office exemption and satisfy the IRS guidelines you need to walk a very, very fine line. Consequently, much of the convenience and simplicity desired from a PTC is lost when put into practice.

Another often-overlooked and extreme cost to a PTC is the change to family dynamics and relationships. Creating and managing a PTC may precipitate stress, anxiety, demand time, or instill intra-family conflict. It forces you to make judgments about your family and have those judgments publicized, at least amongst those members you select to participate in the PTC. For example, the IRS requires you to select some family members to make discretionary distribution decisions for other family members, hence one group dictates both modest decisions (e.g. what car to buy) and major decisions (e.g. funding a beneficiary’s business) for others. You also lose much privacy, as both family members and independent third-parties end up with considerable information regarding your wealth and wishes.

Notwithstanding, the benefits of a PTC cannot be ignored and, therefore, when is it the right choice for you?

Most families that turn to a PTC hope to tailor the trustee experience to their situation, solve problems arising from unique assets and concentrations, fulfill State income tax planning goals, harvest additional deductions, and take advantage of historic personal connections. This tailor-made experience is noticeably more expensive than a boutique, corporate trust company, from which several ultra-high net worth families find the same benefits but share the financial costs.

Boutique, corporate trust companies, which are often regulated by the State, provide the same safeguards and professionalism as corporate trustees without the bulky bureaucracy and inefficiency of large institutions. Using these specialized companies avoids the heavy financial and non-financial costs and burdens of owning a PTC. Moreover, they focus on a narrowed subset of families or trusts to gain expertise in that area. For example, the institution behind this article provides services to a limited group of ultra-high net worth families, which allows it to maintain a high level of individualized service, take on unique asset classes or concentrations and mitigate the risk associated therewith, work with non-residents, and/or administer difficult and complex trust structures.

Each family has different needs and desires and, for that reason, there is no universal option. Large institutions provide secure and standardized services but tend to be inflexible and unaccommodating. PTCs seem to provide the upmost in flexibility but have surprising legal restrictions that create significant costs and destroy privacy. If you find the right fit, a boutique, corporate trust company can provide the best of both worlds.

Wealthgate Trust is a client-founded, Nevada-based, multi-family boutique trust company. Born from the founder’s own experiences searching for an ideal trustee solution for his family, Wealthgate Trust partners with ultra high net worth families and their advisory team to create, implement, and administer bespoke trust strategies.

Wealthgate Trust is licensed and regulated by the Nevada Financial Insurance Division (NFID), and audited separately by the NFID and two national CPA firms.

Aaron is a Wealth Strategist assisting Wealthgate Trust families and their advisors in developing and implementing bespoke estate planning strategies. He’s an attorney licensed to practice in California and Nevada, with over a decade of trust and tax planning experience, and presents on a variety of topics including wealth preservation and private trust companies.

Aaron previously served as the primary tax planning counsel for Lobb & Plewe LLP. He has represented several major trust companies and sits on the board of the Coalition for American Retirement. Aaron earned his JD from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.